Can Bayswater level up with the rest of prime central London?

By Liz Rowlinson

The first stages of the £3bn redevelopment of Queensway are bedding in. More change is on the way. But there’s still some distance to go to shake off the “cheap side of the park” jibes. Buyers are enjoying a different view of Bayswater, as luxury developments such as Park Modern transform the landscape. Can Bayswater level up with the rest of prime central London?

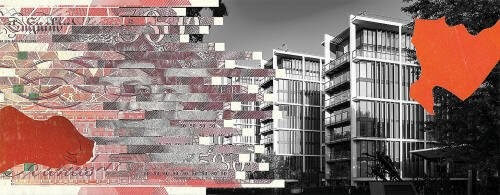

Just north of London’s Hyde Park on Queensway, the main commercial artery of Bayswater, The Whiteley is one of the capital’s most talked-about ultra-luxury apartment schemes. Behind the creamy-white art deco Portland stone facade of what was once London’s oldest department store, are 139 new apartments, a Six Senses hotel, plus shops, restaurants, an Everyman cinema and upscale Third Space gym. Yet, across the street from the Foster + Partners redesigned building (where a penthouse is selling for £39.5mn), it’s a different matter. A block of cheap souvenir shops, discount stores and fast-food joints buzzes about its business. A boarded-up shop reads “Queensway is changing”. After June these will be razed to make way for high-end shops and pavement cafés. But will the £3bn regeneration of the street with Parisian-style glass dining pavilions, help the “cheap side of the Park”, as it is known, level up with the rest of prime central London?

Despite all the elegant Victorian white stucco terraces, pretty garden squares and many a photogenic mews, the neighbourhood between Notting Hill and Marble Arch has, for several generations, been the grittier, under-the-radar sibling in the area — a sort of lost hinterland. Bayswater’s renaissance has been driven by developments such as The Whiteley, a luxury conversion of the former department store into apartments starting at £1.5mn. It was not always so.

When its genteel crescents and squares were built in the 1850s it was a quietly affluent area, where William Whiteley decided to build a drapery shop on Westbourne Grove that became the new Whiteleys store (with royal warrant) in 1911. The area’s desirability continued when Selfridges bought and extended the store in 1927; it also became known for its affluent multiculturalism with its Greek, Jewish and Middle Eastern communities.

But since the 1980s it has drifted downmarket. Bayswater (W2) became the area “where you can get spacious period flats and mansion blocks at a discount for prime central London” says Moreas Madani of Tyburn Property Consultancy. The average flat sold for £1,229 per sq ft last year — considerably less than the prime London average of £1,577, according to LonRes, which tracks the prime market.

But as the wider prime central London market struggles with the effects of Brexit, stamp duty increases, higher mortgage rates and inflation, Bayswater has stayed stable. The average price per sq ft of a sold property fell just 0.1 per cent between 2023 and 2024, while transaction levels were up 9 per cent. The respective averages across prime central London were down 5.6 per cent and up 5 per cent. Average time on the market of 285 days (around nine months) is consistent across both. The drive to regenerate Bayswater has not robbed it of its many quintessentially Victorian properties and businesses.

A new, younger demographic is now seeing the area’s comparative value as “less a compromise and more an opportunity”, says Madani. The smartening up of the area around Paddington Station, used by the Heathrow Express and more recently Crossrail, has already moved the dial.

Daven Chopra who works in finance is about to exchange on a one-bedroom flat in a stucco terrace near Queensway, after living in Maida Vale, an affluent area 1.5 miles north. “I use Heathrow every week and being so close to Paddington was also a big draw — and I am at my Hanover Square office on the Elizabeth Line in around 10 minutes. While some of the incredible buildings in Bayswater are [currently] rundown bedsits or guesthouses, I am confident this will change.”

The opening of Crossrail was also a plus for Jacinta Goulter who bought a one-bed flat in the area after moving from Queens Park, another affluent but less central area. “Being next to the Park has to be a good investment,” she says. She cites a new outpost of pilates brand FORM on Queensway, and Jeremy King’s new restaurant The Park as early signs of positive change. The American-style restaurant is on the ground floor of Park Modern, a super-prime development by Fenton Whelan at the Park end of Queensway, which will bookend a swath of new development running down from The Whiteley. Developments such as Park Modern are driving change.

At 28-34 Queensway, 30 apartments will be completed in early 2026. The company has also acquired the long block opposite The Whiteley which was formerly slated to become The William; it is applying for new planning consent for a seven-storey, Portland stone apartment building with shops and cafés, which will also be given a new name and identity. “We wanted to be part of the transformation of Queensway but are glad The Whiteley got the ball rolling,” says Vabel co-founder Daniel Baliti. “You look at how Notting Hill changed, and then Fitzrovia, then Marylebone and this is next.” He says they are looking to bring in brands and a private members club that are fun, fresh and modern — “less stuffy than Belgravia”.

The Whiteley has been one of Savills’ best-performing new schemes, according to Edward Lewis, head of London residential development for the company, who says that its average £3,600 per sq ft is less than new prime developments in Marylebone (£4,000), and the area including Mayfair, Knightsbridge and Belgravia (£5,000-£6,000). The building has 38 apartments left to sell (from £1.5mn).

Alex Winship The Queensway Steering Group of landowners (including The Whiteley and Fenton Whelan) is overseeing the area’s redevelopment. As well as introducing more street cleaning and security, they are also planning new paving and planting that will lead down to new ornate public gates into Hyde Park. There will also be upgrades to Queensway and Bayswater Underground stations.

A £3mn refurbishment was recently completed at Porchester Spa — London’s joint oldest with York Hall, both opened in 1929. Smaller developers are feeling the ripple effect of the Queensway regeneration. “Right now, Bayswater feels like an easier place to sell a property than Maida Vale,” says Ben Wilson of Knight James, which buy homes to renovate and sell on.

Current projects are in Westbourne Terrace — a wide, tree-lined street of stucco terraces near Paddington — and Gloucester Terrace. “I see Bayswater catching up with Notting Hill in 10 years.” Some people like the idea that W2 is not full of Instagramming tourists asking for directions to Portobello Road Market Charles Irwin, Winkworth Madani of Tyburn Property has not yet seen a rush of buyers reappraising those stucco houses: “The effect so far has been more psychological than transactional.”

Camilla Dell of Black Brick Property Solutions agrees: “I think the area will level up but it will take a while. At the moment it’s a bit of a hard sell. You are still buying with the hope factor.”

Long-term residents are also hopeful, says Scott Joseph of estate agent Anderson Rose. “Since The Whiteley I have had calls from owners in nearby mansion blocks assuming they can sell their flats for double what they are worth — which is actually around £1,000 to £1,300 per sq ft.” The LonRes data would suggest that what Joseph calls a “slim increase in value” is nearer the reality. But even those houses in Bayswater’s most desirable pockets, and which achieve a £1,500 per sq ft price tag, are still at least 25 per cent cheaper than similar properties in Notting Hill, says Charles Irwin of Winkworth, who points to the “lovely little enclave” of Sunderland Terrace, Alexander Street, Durham Terrace and Westbourne Gardens. He has just sold a six-bedroom house in Bayswater, off-market, for £6.35mn that he estimates would be £10mn in prime Notting Hill. He adds: “Some people like the idea that W2 is not full of Instagramming tourists asking for directions to Portobello Road Market.”

Popular private prep schools such as Wetherby, Chepstow House and Pembridge Hall are close by so the large properties of the W2 area are a draw for families. “I can see houses in Bayswater [rising in value] more quickly than flats,” says Irwin. LonRes figures bear this out: the average house in W2 is up 5.6 per cent last year on the pre-pandemic average — more than the 3.5 per cent average of prime central London.

The border between Notting Hill and Bayswater is becoming more blurred in people’s minds, believes Arthur Lintell of Knight Frank’s Notting Hill office, referring to the streets west of Queensway — around Leinster Square, Hereford Road and Ossington Street. “Younger, wealthier buyers, including a number of Americans, want proximity to both Notting Hill and Queensway.” A four-bedroom flat on Cleveland Square, currently under offer through Savills, at £3.25mn Americans have been the biggest group of foreign buyers at The Whiteley, says Charles Leigh, sales director at the scheme. There have also been a number of British downsizers from Notting Hill. “We’ve seen people moving here from a four-storey townhouse within a mile of The Whiteley.” Yet the buzz about the project has had little impact on the area’s rentals market so far. “Until everything’s up and running [on Queensway], I don’t see demand and rates increasing,” says Tanya Hasking, head of lettings at John D Wood. “We are quite some time off that.”

Andrew Norris who has bought a one-bedroom flat on Queensway, opposite Starbucks, is happy to play the long game. “If in time I need a bigger place, I know it will be a great rental investment,” says the surveyor, who moved from Balham, south London. “I bought when it was undervalued but I can see that changing.” Some fear that the changes on Queensway may result in the area losing its distinct appeal and become just another slickly curated high street. But recent buyers such as Chopra feel that a new distinction is needed. “I don’t think there is anything to lose. I hope it becomes like Westbourne Grove — my favourite street in London.”