By George Hammond

A growing number of investors who bought new homes to sell on for a profit have got their fingers burnt

In Earls Court, west London, there is a flat that has just been built. Before anyone even moved in, this three-bedroom apartment had three different owners, and lost one of them almost £400,000.

The flat is part of what will be an 808-home project in Lillie Square, co-developed by Capital & Counties Properties and members of Hong Kong’s Kwok family. The scheme’s first phase went on the market in March 2014, just as property prices in London were beginning to crest.

The developers quickly found a buyer for the flat, who took on a £2.07m contract to pay for what was then merely a picture in a glossy brochure. The buyer’s hope was that it would grow in value and could be sold on — perhaps before it was even finished.

But then London’s high-end market turned and prices fell. Unable to complete on their contract, the buyer of the Lillie Square flat sold last month for £1.7m, 18 per cent less than they had paid the developer.

Buying unfinished property and aiming to sell it on quickly for a profit — known as flipping — was a safe bet in London immediately after the recession. Now, the odds have changed.

As prices fall, many property flippers are unable or unwilling to complete, so face either selling at a loss or losing their deposit, says Camilla Dell, founder of buying agency Black Brick, which represented the most recent acquirer of the Lillie Square apartment.

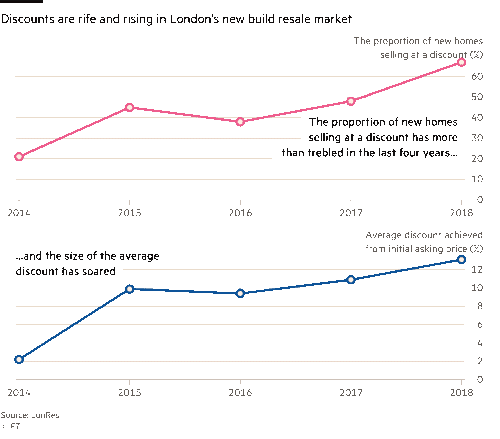

In 2014, 21 per cent of resales in recently completed developments were sold at a discount, according to property research company LonRes. Last year that number had more than trebled, to 67 per cent. At the same time, the size of discounts has ballooned. From an average of 2.2 per cent in 2014, to 13.1 per cent last year.

In some places, the markdown can be double that. “It’s 15-20 per cent in prime central London. South of the river it can be 25 per cent or upwards,” says Charlie Ellingworth, a founder of buying agents Property Vision. For dollar buyers, the falling value of the pound means “you could be talking about [a discount of] 40 per cent”, he adds.

Off-plan investors often rely on a process called assignment, where the right to complete a purchase is sold to a new buyer. Typically, the original party, the “assignor”, will have paid only a deposit to the developer when they contracted to buy off-plan and in assigning their rights under the contract they are looking to recoup their downpayment and more. Because stamp duty is paid on completion, this is another overhead that can be avoided by assignors.

A seller in One Blackfriars has taken a hit of nearly £1m.

When prices were increasing, such transactions could provide handsome returns for assignors, without them ever being responsible for the physical property. Riverlight, a high-end Berkeley Group development in Vauxhall launched in 2011 and was completed in 2017. Soon after it went on sale, deposits were put down on two-bedroom apartments that cost roughly £700,000, says Andrew Griffith, managing director of estate agency MyLondonHome, which has sold a number of flats in the scheme. Two or three years later, they were able to sell on those homes for up to £1.2m.

It is hard to get a sense of the current scale of London’s assignment market. Resellers value discretion and properties resold on the assignment market do not appear in Land Registry figures.

But a ring around agents marketing homes in the Thames-side Nine Elms development suggests flippers are common. One estate agency is listing four apartments in The Dumont, a Berkeley Group development that is not set for completion until 2020. How many of the listings are resales? All of them.

Next door in the Corniche, another Berkeley scheme, all but one of the properties listed by estate agency MyLondonHome are resales. “Most of them are people who’ve bought direct through the developer and want to avoid the stamp duty,” says Griffith. One buyer who paid close to £900,000 is now willing to sell for £100,000 less, he adds.

In the recently completed One Blackfriars — a glass monolith that towers over Blackfriars Bridge — one seller has taken a hit closer to £1m. Having put down the deposit for a £3.021m, three-bedroom apartment, they sold it before it was finished, for £2.25m.

“During the last bull market, many investors were exchanging on off-plan new-build properties with a view to re-assigning their contract for profit ahead of completion,” says Chris Jones, director of buying agency Warnerheath. With falling property prices, some investors have come unstuck, he adds.

The price you negotiate off-plan is the price you pay at the end, even if the market has fallen 30 per cent.

As well as speculators on the assignment market, there are plenty who will have taken out substantial loans to cover their acquisitions. Between April 2014 and March 2016, more than half of all overseas buyers in London’s new-build market took on a mortgage, according to research from the University of York.

“A lot of these overseas buyers are not cash-rich oligarchs or sheikhs, they’re middle-class Singaporeans or Malaysians, [people from] Hong Kong or mainland Chinese”, says Neal Hudson, director at Residential Analysts.

Some of those buyers will be “pretty unsophisticated”, says Ellingworth, and might well have agreed to a purchase “in a hotel in Hong Kong”.

Having done so, they have little protection against falling prices. “The price you negotiate off-plan is the price you pay at the end, even if the market has fallen 30 per cent. Your mortgage lender doesn’t care if it’s gone down. As the buyer, you can inject the equity yourself, or you fail to complete,” says Dell.

Distressed sellers are unlikely to be the only ones touting discounts. “The developers who want to offload their stock are undercutting the flippers,” says Jo Eccles, founder of buying agency SP Property Group.

Two-bedroom apartments in Riverlight, a Berkeley Group development in Vauxhall, launched in 2011 for a price around £700,000. Two or three years later, they sold for up to £1.2m.

Slashing prices is a last resort for developers, who will instead dangle add-ons such as “a beautiful furniture pack or a parking space worth £75,000”, says Eccles. Even so, she says, a number of developers are accepting lowball offers in order to meet sales targets.

“We’re beginning to see 20-30 per cent [reductions] being considered by developers”, says Jones, who typically acts for clients buying in bulk. “Developers are looking to get deals done.”

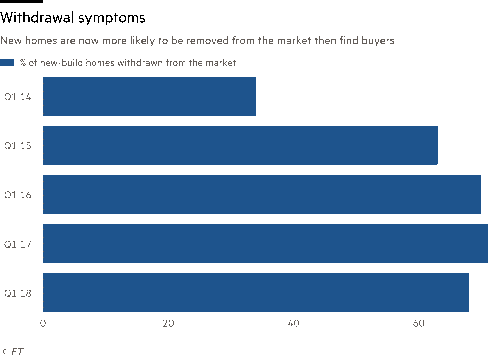

Faced with selling at a loss, a growing number are opting to take the “for sale” signs down and are falling back on the rental market or taking up residence. LonRes report that 68 per cent of the recently completed flats that came off the market last year were removed because of withdrawal rather than sale — compared with 34 per cent in 2014.

Rather than resigning to the downturn, some see opportunity. On a recent property search in west London, reports Jones, “it was very clear across the board that a lot of sellers had overpaid in 2014 and 2015”. Now, a number of them are actively looking to sell at a discount.

Their eagerness is not borne of financial distress: they want to upsize. If the market is down 20 per cent across the board, a £200,000 hit on a £1m home will be more than offset by a £400,000 discount on something twice the price. Those lucky enough to afford the trade-up might find a few sellers desperate to transact, even at a loss.